Editing.

We all do it, whether you’re a writer, painter, composer, film maker, designer. It is an important stage in any discipline. But despite its crucial role in the creative process, it feels verbally neglected.

So, let’s talk about editing!

Last summer I treated myself to a course at the Music Summer School Festival in Holt (formerly Dartington). I joined a course titled Making In Sound And Vision. It was run by composer Stephen Montague and artist Alex Julyan, and examined the way in which music and sculpture can become entwined, using the sculpture as a 3D graphic score.

We discussed the shared creative practices used in both disciplines - defining a concept, setting parameters for the scale of the work (size or duration), thinking about shape and form, editing etc. It was interesting to note that, though creating through different mediums (art vs music), we use the same principles.

I found the course very inspiring, it gave me a lot of food for thought. But the discussion which stayed with me the most was the one about editing.

When creating anything, we have to experiment, to take risks. We also have to ask ourselves “does this work?” When we reach the end of a first draft, it is important to take a step back and ask questions like “does this piece fulfil my intentions? Have my intentions evolved throughout the process? Does the piece say what I want it to say? Have I strayed too far from my original idea?”

I have always asked myself “does this work?” and “has my intention changed?” but, if I’m being honest, I haven’t been as good with questions like “does this piece fulfil my intentions? Does it say what I want to say? Have I lost sight of the aim?”

For me, one of the most important lessons I took from the course was this: editing is almost always the removal of material, not the addition of more. It sounds obvious, but I am definitely guilty of thinking “hmmm this isn’t working.. I know, I’ll add something to compliment x,” instead of “there’s too much material. Take out x and use it for a different piece.”

Editing can be brutal. It can feel incredible disheartening to see hours, days, weeks worth of work cast aside so quickly. It can feel like you’re going backwards. But try not to feel too downcast. Experimentation is an important part of the creative process. It’s where we learn. We learn what we do and don’t like. We learn what the piece shouldn’t be. We might discover amazing new sound combinations which would be great for an entirely different project. Like anything, we can learn more from a mistake than an instant success. That brutal cull of your work evolves the piece to a polished, pure, uncluttered shine.

I remember one course participant in particular who struggled with the idea of experimenting and editing. She couldn’t get past the idea of removing material from her sculpture. “What was the point in putting it on in the first place if I’m just going to take it off again!?” she despaired.

The discarded material doesn’t have to be binned, but can be shelved for a more suitable piece of work.

Why am I writing this now, nearly a year on?

Well, I’ve recently had a reminder of why editing is so important.

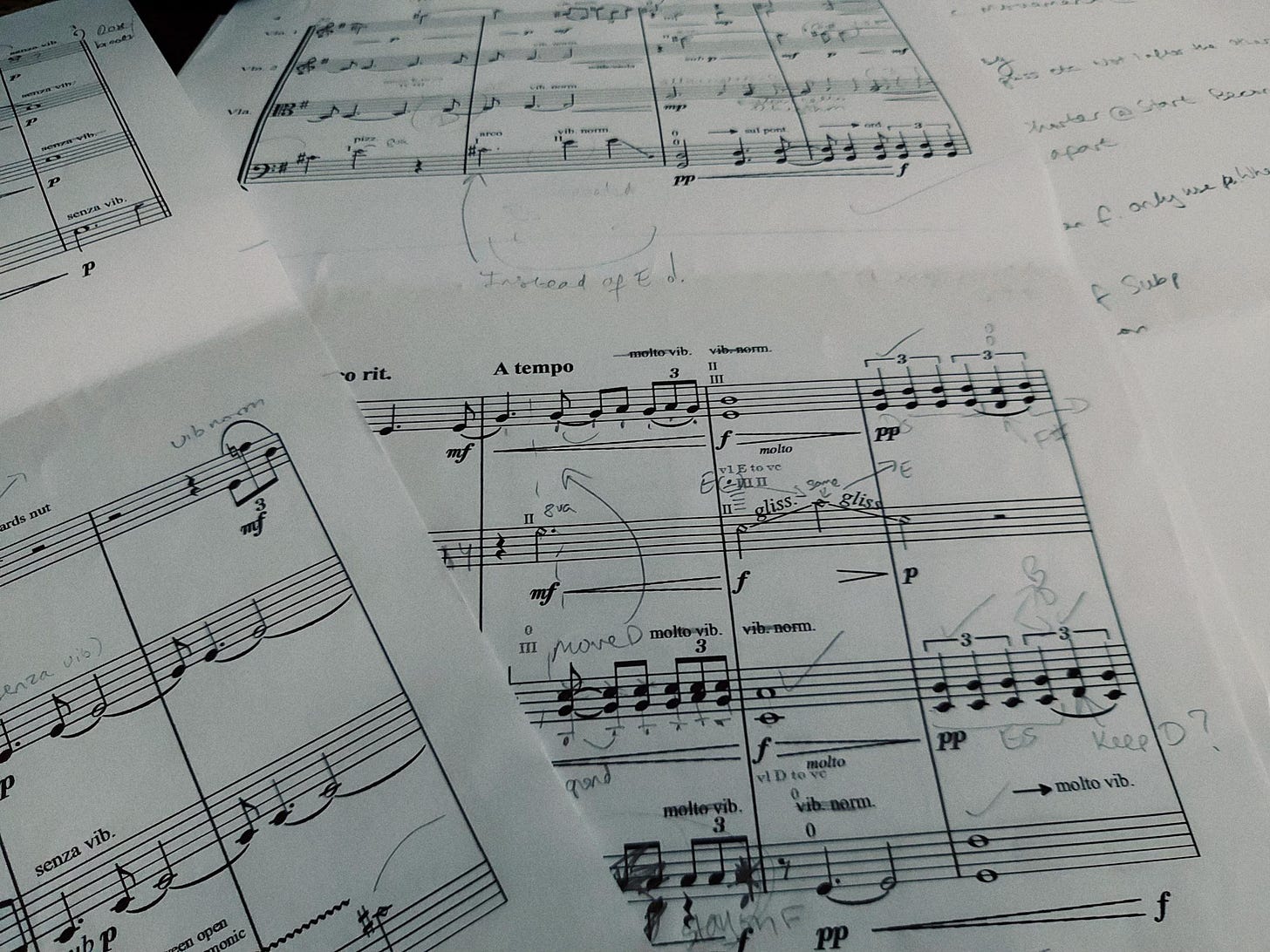

Earlier this year, I had a piece for string quartet workshopped. I received the recording last month, hearing the piece outside of my head for the first time. My reaction was not what I expected - Oh god! Take it all out!

The piece is called Stasis. I wrote it in 2020 (remember that year?). It is supposed to embody the feeling of time standing still, all the days blurring into one another, yet this feeling of stillness is undermined by the fact that the year is actually moving forward as normal, with or without our cognitive realisation.

I intended to explore delicate textures, harmonics, and timbral trills, against a canvas of very slow, or almost none existent, harmonic progression. I wanted to create a sense of suspended time with occasional interruptions of tension. Instead, my piece sounded busy and chaotic - the complete opposite of what I had planned!

So how did I get it so wrong?

Unpicking my composing process, I think I have found where it all unravelled.

The first draft was just as I wanted: slow moving, sustained notes with timbral changes. But I began to second guess myself. What if it was too boring? Boring for the listener, boring for the performers? Maybe I should add some rhythmic movement. Maybe I should occasionally hint at a melodic line. Maybe I need more independent entries and more effects.

I added them all.

I became so focused on the piece not being boring that I lost sight of my intentions. I was so desperate for solutions that I was grabbing from anywhere, completely overlooking those that would have been in keeping with the aim of my work. I used everything in my musical tool box instead of being selective.

So now I’m going to edit the hell out of this work! I will take everything out, strip it right back to the bare bones and, with the aid of the workshop recording, work out which small and sporadic details are needed where.

On a slightly separate note, this also shows how important workshops are. Because no amount of my imagination, Sibelius playback (insert skull emoji here), or my playing on the piano, accurately represented the string quartet which I’d written.

Closing thoughts

Less is more….Sometimes.

I’m not saying make a slow moving minimalistic piece. I mean get rid of anything which clouds the intention or undermines the message of your work.

Focus on one thing at once. If you have loads of amazing ideas, that’s great. If they don’t compliment each other, turn them into different pieces.

We don’t all get it right all of the time. Even the highest level professionals. I’ve been to concerts with composition tutors and we’ve both come away saying “there were some really nice moments in that piece but my god it was loooooooonng! It needs cutting down by half.” So if you’re struggling with your edits, don’t beat yourself up. Just take a step back and try to remember the following:

Don’t bury the intended message

Clear the clutter and remove the unnecessary

Check to see if you’ve lost sight of the original idea

Take a small piece of material, or one idea, and exploit it for all its worth.

And you can totally follow these principles for a really OTT maximalist piece of work, because the important thing is knowing and following your intentions.

As I said at the start, these principles don’t solely apply to music. They can be used in any medium: writing, whether academic or recreational; visual arts; dance; architecture; the list is endless. And yes, this particular piece of writing has gone through several edits before reaching you today!

So, I invite you to take a step back from your most recent work-in-progress, look at it with fresh eyes, and ask yourself, “Are my intentions clear?”